- Home

- Hunt, Tristram

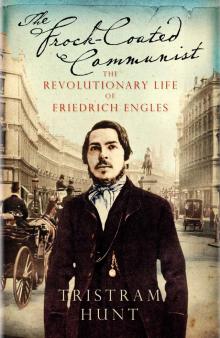

Frock-Coated Communist Page 5

Frock-Coated Communist Read online

Page 5

I, too, am one of Freedom's minstrel band.

‘Twas to the boughs of Börne's great oak-tree

I soared, when in the vales the despot's hand

Tightened the strangling chains round Germany.

Yes, I am one of those plucky birds that make

Their course through Freedom's bright aethereal sea…

Shelley's Philhellenic epic Hellas similarly appealed to his accelerating nationalism. Indeed, the cause of Greek independence was a popular one in the Rhineland as dozens of local associations sprang up to assist in the 1820s struggle against the Ottomans, with the conflict used as something of a proxy for enthusiasts of Germany's own quest for national autonomy.49 Engels himself had earlier penned a piece of narrative fiction, ‘A Pirate Tale’, which whimsically recounted a young man's struggle against the Turks and his ‘fight for the freedom of the Hellenes… men who still have a taste for freedom’.50 On multiple levels, the life and work of Shelley served as a source of inspiration for Engels and, stuck in Bremen during a dull summer in 1840, he even made plans to publish his own translations of The Sensitive Plant. Later, he would reveal to Eleanor Marx that at that time ‘we all knew Shelley by heart’.51

Less loftily, developments in France were also sharpening Engels's political stance. He did not yet regard 1789 as the epoch-making event he later would and, at this stage, he was more enamoured of the bourgeois revolution of July 1830 – which had seen the ejection of King Charles X and his replacement with the constitutional monarch Louis-Philippe. For Young Germany, this had been the supreme example of ‘freedom’ in action. ‘Each item was a sunbeam, wrapped in printed paper, and together they kindled my soul into a wild glow,’ recalled Heine of receiving the news. ‘Lafayette, the tricolor, the Marseillaise – it intoxicates me. Bold, ardent hopes spring up, like trees with golden fruit…’52 Along the industrial settlements of the Rhineland, Paris's successful deployment of popular will against an aloof monarch was widely celebrated in a series of anti-Prussian riots. Once reviled for its occupation of the Rhineland, but now admired again for its national liberation, France and its July days stood for the overthrow of antiquated authoritarianism in the name of progress, freedom and patriotism. Compared with the revolutionary communism of his coming years, Engels's support for this bourgeois constitutionalism – with its commitment to the rule of law, the balance of power, the freedom of the press – was fairly mild stuff. But, at the time, it was exhilarating enough. ‘I must become a Young German or rather, I am one already, body and soul,’ he wrote in 1839. ‘I cannot sleep at night, all because of the ideas of the century. When I am at the post-office and look at the Prussian coat of arms, I am seized with the spirit of freedom. Every time I look at a newspaper I hunt for advances of freedom.’53

In his free time in Bremen between the socializing, the Trevinarus family fun and games and the counting house, for the first time Engels began to write publicly of his hunt for freedom. Historically, Engels's style has been deemed inferior to Marx's: commentators are given to contrast the leaden, clinical prose of Engels with Marx's glittering, chiasmus-ridden wit. This is unfair. For Engels was, in fact, an elegant author in both his private and public writings until his work took a more doggedly scientific turn in the 1880s. That said, the case for the defence does not begin promisingly.

Sons of the desert, proud and free,

Walk on to greet us, face to face;

But pride is vanished utterly,

And freedom lost without a trace.

They jump at money's beck and call

(As once that had from dune to dune

Bounded for joy). They're silent, all,

Save one who sings a dirge-like tune…

‘The Bedouin’ – Engels's first published work – was an Orientalist poem eulogizing the noble savagery of the Bedouin people undone by their contact with Western civilization. Where once they walked ‘proud and free’, now they slavishly performed for pennies in Parisian theatres. Even for an eighteen-year-old it was a clumsy effort. Still it showed that under the dull routine of his commercial correspondence, Engels retained his romantic, Shelley-like ambitions. The work was, in fact, something of a tribute to Wuppertal's most celebrated poet-clerk, Ferdinand Freiligrath, who combined his work in the Barmen firm of Eynern & Sohne with a flourishing literary career. From the provincial banality of the Rhineland, Freiligrath conjured up a dreamland of exoticized tribes and sun-drenched landscapes typically peopled by beautiful Negro princesses. Engels the bored clerk was enchanted and in numerous verses he shamelessly ripped off Freiligrath's tropes of Moorish princes, proud savagery and corrupt civilizations.

Yet he could not shake his youthful literary passion for the German mythical past and, in April 1839, he penned an (unfinished) epic play based around the life of the folk-hero Siegfried. It is full of demands for action and an end to reflection with battles entered and dragons slain. Most intriguing is the stress Engels lays on the psychological struggle between Siegfried and his father, Sieghard: while the former wants to run free (‘Give me a charger and a sword / That I may fare to some far land / As I so often have implored’), the king thinks ‘it's time he learned to be his age’ (‘Instead of studying state affairs / He's after wrestling bouts with bears’). After a war of words, the father finally lets go and Siegfried is free to follow his own path in life (‘I want to be like the mountain stream / Clearing my route all on my own’). It doesn't require too much psychological insight to realize that, in the words of Gustav Mayer, this unfinished play represents ‘the virtual embodiment of the battle that may have taken place in the Engels family in relation to Friedrich's choice of vocation’.54

More successful than his poetry was Engels's journalistic prose. ‘The Bedouin’ had been published in the Bremen paper Bremisches Conversationsblatt, and Engels – like any good hack – had immediately complained about the subs ruining his copy (‘the fellow went and changed the last verse and so created the most hopeless confusion’). 55 So he moved on to write for Karl Gutzkow's paper, Telegraph für Deutschland, and began to make his name as a precocious cultural critic from the Young Germany stable. Or rather, he began to make the name of his chosen, suitably medieval-sounding pseudonym, ‘Friedrich Oswald’ – an early indication of the tensions which would come to mark Engels's life. He wanted his opinions and criticisms to be heard, but at the same time he was keen to avoid the stress and anguish which would inevitably come from any open break with his family's values. For both his own financial security and his unwillingness to embarrass his parents publicly, Engels started out on his double life as ‘Oswald’

The Telegraph's in-house style was the feuilleton: unable, due to Prussian censorship, to publish detailed political commentaries, the progressive papers embedded their criticism in literary and cultural pieces, even travelogues. The writer became an intellectual flâneur, interspersing social and political points among reflections on regional culture and cuisine, memory and myth. Landscapes, boat journeys and poetry provided Engels with just the romantic cover he needed to expound his liberal, nationalist sensibilities. Thus a travelogue on Xanten, ‘Siegfried's Native Town’, allowed Engels to mount a critique of conservatism in the name of freedom and youth. As our correspondent enters the town, the sound of High Mass filters from the cathedral. For the emotional ‘Oswald’ the sentiments are almost too much to take. ‘You, too, son of the nineteenth century, let your heart be conquered by them – these sounds have enthralled stronger and wilder men than you!’ He gives himself up to the myth of Siegfried, drawing from it a modern message: the need for energy, action and heroic contempt in the face of the petty, deadening bureaucracy of the Prussian state and its newly ascended monarch – the religio-conservative Frederick William IV. ‘Siegfried is the representative of German youth. All of us, who still carry in our breast a heart unfettered by the restraints of life, know what that means.’56

Engels's most substantive writing for the Telegraph was markedly less high-flown

. During the 1830s the Rhineland textile industry was finding it increasingly difficult to challenge the industrialized English competition. The old-fashioned outwork practices of the Barmen artisans – with textile goods produced by hand in home workshops – were proving no match for the efficient, mechanized manufactories of Lancashire. Even within Germany, with its free trade Zollverein (Prussia-led Customs Union), the situation was bleak as the Rhenish advantage in textile goods fell away to competition from Saxony and Silesia. French demand for silk weaving and ribbon took up some of the slack, but it was a volatile, fashion-driven market subject to sharp drops in demand. These economic changes brought a steady worsening of conditions among Barmen workers and the gradual disintegration of the kind of paternalist corporate structures that the Engels family had traditionally prided itself on. Guilds were disbanded, incomes squeezed, working conditions undermined and the old social economy of apprenticeships, wage differentials linked to skill levels and properly paid male labour came under sustained assault. In their place sprang up a stark, new divide between worker and manufacturer which for those on the edges of the textile economy – handspinners, hosiers and weavers – meant a rapid diminishment of income and position.

This new economic reality was reflected in the growing usage of the terms ‘pauperism’ and ‘proletariat’ by journalists and social commentators in referring to the kind of rootless, propertyless, casual urban workers who lacked regular employment and security: the thousands of unemployed and under-employed knife-grinders, shoemakers, tailors, journeymen and textile labourers who crowded into the towns and cities of the Rhineland. In cities such as Cologne between 20 and 30 per cent of the population were on poor relief. The German social theorist Robert von Mohl described the modern factory worker – unlikely ever to be apprenticed, to become a master, inherit property or acquire a skill – as akin to a ‘serf, chained like Ixion to his wheel’. The political reformer Theodor von Schon used proletariat as a synonym for ‘people without home or property’.57

‘Friedrich Oswald’, however, did something rather different. In a style he would in the coming years define as his own, Engels got amongst the people to produce an extraordinarily mature piece of social and cultural reportage. No lofty social theories about the nature of pauperism and the meaning of the proletariat for this son of a factory owner. Instead his ‘Letters from Wuppertal’ – published in the Telegraph in 1839 – offered an unrivalled authenticity, an eye-witness experience of the depressed, drunken, demoralized region. When Engels contrasted the reality of Barmen life with his romanticized ideal of what the motherland was meant to be – the imagined nation of Herder, Fichte and the Brothers Grimm peopled by a lusty, patriotic Volk – the disappointment was tangible. ‘There is no trace here of the wholesome, vigorous life of the people that exists almost everywhere in Germany. True, at first glance it seems otherwise, for every evening you can hear merry fellows strolling through the streets singing their songs, but they are the most vulgar, obscene songs that ever came from drunken mouths; one never hears any of the folk-songs which are so familiar throughout Germany and of which we have every right to be proud.’58

Written by a nineteen-year-old industrial heir, the Letters provided a magnificently brutal critique of the human costs of capitalism. Engels points to the red-dyed Wupper, the ‘smoky factory buildings and yarn-strewn bleaching yards’; he traces the plight of the weavers bent over their looms and the factory workers ‘in low rooms where people breathe in more coal fumes and dust than oxygen’; he laments the exploitation of children and the grinding poverty of those he would later term the lumpenproletariat (‘totally demoralized people, with no fixed abode or definite employment, who crawl out of their refuges, haystacks, stables, etc., at dawn, if they have not spent the night on a dungheap or on a staircase’); and he charts the rampant alcoholism amongst the leather-workers, where three out of five die from excess schnapps consumption. Decades on, this memory of industrializing Barmen continued to haunt him. ‘I can still well remember how, at the end of the 1820s, the low cost of schnapps suddenly overtook the industrial area of the Lower Rhine and the Mark,’ Engels wrote in an 1876 essay on the social effects of cheap alcohol. ‘In the Berg country particularly, and most notably in Elberfeld-Barmen, the mass of the working population fell victim to drink. From nine in the evening, in great crowds and arm in arm, taking up the whole width of the street, the “soused men” tottered their way, bawling discordantly, from one inn to the other and finally back home.’59

The Letters’ prose was biting, but did the high-living and studiously intellectual Engels, the moustachioed fencer and feuilleton author, feel any personal empathy for these Wuppertal unfortunates? Official communist biographies are unequivocal that Engels's politics ‘rested on a profound and genuine feeling of responsibility vis-á-vis the lot of the working people. Their sufferings grieved Engels who was anything but a prosaic, cold, matter-of-fact person.’60 Certainly, any reader of Engels's work always takes away a clear picture of injustice and its causes, but whether the author was emotionally affected or merely ideologically motivated by such misery remains unclear. At this stage, all that can be said is that his strength of feeling for the Barmen underclass was probably as much the product of a rebellious antagonism towards his father's generation as any considered sentiment for the workers’ plight.

Whatever the motivation, the criticisms cascaded down the Telegraph columns – as if carefully noted and steadily accumulated since childhood. The miserly vulgarity of the Wuppertal employers was reflected in the town's design, with ‘dull streets, devoid of all character’, shoddy churches and half-completed civic monuments. To the now sophisticated eye of the Bremen-based Engels, the town's so-called educated elite were nothing more than philistines. There was precious little talk of Young Germany along the Wupper valley, which was filled instead with endless useless gossip about horses, dogs and servants. ‘The life these people lead is terrible, yet they are so satisfied with it; in the daytime they immerse themselves in their accounts with a passion and interest that is hard to believe; in the evening at an appointed hour they turn up at social gatherings where they play cards, talk politics and smoke, and then leave for home at the stroke of nine.’ And the worst of it? ‘Fathers zealously bring up their sons along these lines, sons who show every promise of following in their fathers’ footstep It was already apparent that that was not a fate Engels was willing to chance.

Despite the Letters’ critique of working conditions and the social costs of industrialization, Engels's real target was not capitalism per se. He had as yet no real understanding of the workings of private property, the division of labour or the nature of surplus labour value. The true focus of his ire was the religious Pietism of his childhood. Here was a conscious, studied rejection of the guiding ethic behind his family's lineage by a young man disgusted at the social costs of religious dogma. Learning, reason and progress were all stunted by the deadening, sanctimonious grip of Krummacher and his congregations. And the factory workers were embracing the pietist fervour in the same way they consumed their schnapps: as a mystical route out of their all-enveloping misery. Meanwhile those manufacturers who most ostentatiously advertised their godliness were well known as the most exploitative of employers whose personal sense of election seemed to absolve them of the need to abide by respectable human conduct. To Engels the romantic ideologue, Wuppertal was sinking beneath a tide of moral and spiritual hypocrisy. ‘This whole region is submerged in a sea of pietism and philistinism, from which rise no beautiful, flower-covered islands.’61

‘Ha, ha, ha! Do you know who wrote the article in the Telegraph? The author is the writer of these lines, but I advise you not to say anything about it, I could get into a hell of a lot of trouble.’ Engels's ‘Letters from Wuppertal’ sparked a highly gratifying public storm along the Wupper valley. The personal criticism of Krummacher, together with the linkage of Pietism and poverty, was strong stuff – and, though delighted by the controversy, �

�Friedrich Oswald’ was not quite ready to be exposed as one of Barmen's leading sons. Instead, he was content to enjoy a knowing chuckle with some Wuppertal friends from the safety of Bremen.62 His correspondents were his old class mates the Graeber brothers – Friedrich and William – sons of an Orthodox priest and themselves training for the priesthood. Through a typically candid series of letters which Engels wrote to them between 1839 and 1841, we are offered an insight into the most important intellectual shift of Engels's Bremen years: his loss of faith.

It is a cliché of nineteenth-century intellectual historiography that the road to socialism was paved by secularism. From Robert Owen to Beatrice Webb to Annie Besant, the disavowal of Christianity was a familiar rite of passage for those whose spiritual journey would culminate with the new religion of humanity. But its obviousness does not invalidate its truth. ‘Well, I have never been a Pietist. I have been a mystic for a while, but those are tempi passati. I am now an honest, and in comparison with others very liberal, super-naturalist’ was how Engels described his religious temperament to the Graebers in April 1839. He had long been dissatisfied with the narrow spiritualism offered by Wuppertal Pietism, but he remained, aged nineteen, a long way from rejecting the central tenets of Christianity. However, amidst the intellectual liberalism of Bremen life, Engels felt he now wanted more from his Church than predestination and damnation. He was increasingly troubled with the notion of original sin and hoped somehow to unite his Christian inheritance with the progressive, rationalist thinking he had absorbed from Young Germany. ‘I want to tell you quite plainly,’ he informed Friedrich Graeber, ‘that I have now reached a point where I can only regard as divine a teaching which can stand the test of reason,’ before then pointing out the numerous contradictions within the Bible, querying God's divine mercy and taking special delight in exposing a series of astronomical howlers in a recent Krummacher sermon.63

Frock-Coated Communist

Frock-Coated Communist