- Home

- Hunt, Tristram

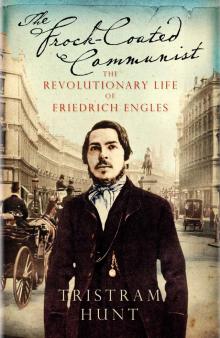

Frock-Coated Communist Page 4

Frock-Coated Communist Read online

Page 4

Behind the poetry and folk-tales, the operas and novels rumbled the hard-edged politics of Romanticism. When peace finally came to Europe in 1815, following Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Waterloo and the ensuing diplomatic carve-up at the Congress of Vienna, the Rhineland was annexed from France by Prussia. The free-thinking, industrial, urban world of the Rhine now fell subject to the Hohenzollern monarchy of Berlin and its dry, Junker ethos which set the merits of hierarchy and authority far above any democratic German culture. Yet across Prussia – as well as within the other principalities, kingdoms and free cities which would later constitute Germany – romantic, progressive patriots raised on the poetry of Novalis and nationalism of Fichte were mobilizing in support of a more unitary, more liberal German nation. Inspired by the legends and language of invented tradition, radicals now wanted to cleanse the memory of French occupation and Enlightenment hubris with a re-invigoration of national sentiment.

From 1815 in Jena, student Burschenschaften (fraternities or clubs) started to campaign for constitutional reform based on the idea of a Germanic patria. They decked themselves out in the black, red and gold colours of the Lützow volunteers (a patriotic Free Corps supposedly made up of armed students and intellectuals who heroically fought the French at the 1813 Battle of Leipzig) and swore loyalty to the fatherland – rather than to the indecisive Prussian King Frederick William III, who was then retreating from his earlier plans for constitutional reform. Part of this patriotic cult found expression in the 150 gymnastics clubs and 100,000-strong choral society movement which sprouted across Prussia, singing ballads and organizing festivals in praise of the fatherland. The movement's high point arrived in October 1817, when students from all over Germany gathered at Wartburg Castle (where Martin Luther had translated the New Testament into German) to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Reformation and fourth anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig. Through a radical political culture built around a strong set of patriotic symbols, the Prussian war against Napoleon was being woven into a broader narrative of emerging German nationhood.32

All of which was deeply troubling to the kings and first ministers of Austria and the German Confederation, who fervently believed in dynasties not nations, monarchies not democracies. They responded with the Karlsbad Decrees of November 1819, which closed down the student societies, ended any talk of a written constitution, put the universities under police surveillance and quashed press freedoms. The 1820s then witnessed an accomplished campaign on behalf of the royal houses to snuff out the radicalism of German Romanticism – masterminded by the Machiavellian Austrian chief minister, Count Klemens von Metternich, whose relentless fear-mongering exercised a remarkable sway over the Prussian authorities.

How much of this Romanticism made its way into Barmen, that inward-looking Zion of the obscurantists? Here, remember, Goethe was just ‘a godless man’. Yet encouraged by Dr Clausen and his own reading of medieval romances, the imagination of young Friedrich Engels was enlivened by this revival of German nationalism. In 1836 he penned a small poem altogether less godly than his Confirmation ode, eulogizing the deeds of such romantic legends as ‘The Archer, William Tell’, ‘The warrior-knight Bouillon’ and ‘Siegfried’, the dragon-slaying hero of the medieval Song of the Niebelungs. He wrote articles championing the democratic tradition of the German Volksbüchner and the work of the Brothers Grimm. ‘These old popular books with their old-fashioned tone, their misprints and their poor woodcuts have for me an extraordinary, poetic charm,’ he announced airily, ‘they transport me from our artificial modern “conditions, confusions and fine distinctions” into a world which is much closer to nature.’33 There were more poems venerating the life of the German national icon and father of printing, Johannes Gutenberg, and even pantheistic accounts of the divine glory of the German countryside (‘gaze over the vine-fragrant valley of the Rhine, the distant blue mountains merging with the horizon, the green fields and vineyards flooded with golden sunlight…’).34 Throughout his long life, Engels never abandoned this youthful cultural patriotism. Even when he was championing the international solidarity of the proletariat and banned on pain of execution from his homeland, Engels retained an unexpected emotional empathy for the heroic world of Siegfried and the epic destiny he represented.

But it was never a sympathy shared by his father. Despite Engels's wish to stay on in school and glowing reports from his headmaster, in 1837 he was summarily withdrawn from the Gymnasium and ushered into the family business. Already concerned about his son's literary foibles and questionable piety, Engels senior had no qualms about removing him from the deviant intellectual circles surrounding Dr Clausen. Friedrich's hopes of studying law at university, perhaps entering the civil service, even becoming a poet – all hinted at in his final report from headmaster J. C. L. Hantschke, who spoke of how Engels was ‘induced to choose [business] as his outward profession in life instead of the studies he had earlier intended’ – were not to be.35 Instead, for an arduous twelve months he was inducted into the dull mysteries of linen and cotton, spinning and weaving, bleaching and dyeing. In the summer of 1838 father and son embarked on a business trip around England to arrange silk sales in Manchester, grège (raw silk) purchases in London, and to look over the Ermen & Engels concerns. They returned via the northern German city of Bremen where Friedrich was set to embark on the next stage of his commercial apprenticeship: a crash course in international capitalism.

The coastal air of Bremen, a free town and Hanseatic trading city, proved altogether more congenial to Engels than the low Barmen mists. Of course, it too was a place of piety (‘their hearts have been scrubbed with the teachings of Johann Calvin,’ complained a resident of his fellow citizens), but as one of Germany's largest ports it was a centre of intellectual as well as commercial exchange. Apprenticed to the Saxon consul and linen exporter Heinrich Leupold, Engels worked as a clerk in the trading house and lodged with a friendly clergyman, Georg Gottfried Trevinarus. After the suffocating Biedermeier gentility of Barmen, the more relaxed Trevinarus household seemed a riot. ‘We put a ring in a cup of flour and then played the well-known game of trying to get it out with your mouth,’ he wrote to one of his sisters about a Sunday afternoon pastime.

We all had a turn – the Pastor's wife, the girls, the painter and I too, while the Pastor sat in the corner on the sofa and watched the fun through a cloud of cigar smoke. The Pastor's wife couldn't stop laughing as she tried to get it out and covered herself with flour over and over… Afterwards we threw flour in each other's faces. I blackened my face with cork, at which they all laughed, and when I started to laugh, that made them laugh all the more and all the louder.36

Engels's Bremen correspondence was a riot of doodles, puns and self-absorption. A letter of 6–9 December 1840 to Marie Engels.

This was just one of a series of letters to his favourite sibling, his younger sister or ‘goose’, Marie. They reveal a part of Engels's character which remained constant throughout his years: a roguish, gossipy, sometimes malicious sense of humour (which would meet its counterpart in Karl Marx) and an uncomplicated appetite for life. His correspondence is littered with nicknames, terrible puns, jottings, even musical chords, together with bragging accounts of doomed romances, alcoholic endurance and practical jokes. Unlike the cyclically despondent Marx, Engels rarely suffered from low spirits. Physically and intellectually, Engels was a Victorian man of action rather than of emotional reflection. Whether it was learning a new language, devouring a library or pursuing his Teutonic urge for hiking, Engels needed to be on the move, channelling his restless energies into seeking out the best of any situation. As the Victorian radical George Julian Harney noted, ‘there was nothing of the “stuck-up” or “standoffishness” about him… He was himself laughter-loving, and his laughter was contagious. A joy inspirer, he made all around him share his happy mood.’37

Engels's work in Bremen mainly involved handling international correspondence: there were packages to Havana, letter

s to Baltimore, hams to the West Indies and a consignment of Domingo coffee beans from Haiti (‘which has a light tinge of green, but is usually grey and in which for every ten good beans, there are four bad ones, six stones and a half ounce of dirt…’).38 Through this clerking apprenticeship, he came to know the ins and outs of the export business, currency deals, and import duties – a detailed knowledge of capitalist mechanics which would, in years to come, prove of great worth to him as both businessman and communist. But for a wistful, young romantic like Engels, it was numbing stuff. And, as his father no doubt warned, idle hands made easy work for the devil. ‘We now have a complete stock of beer in the office; under the table, behind the stove, behind the cupboard, everywhere are beer bottles,’ he boasted to Marie. ‘Up to now it was always very annoying to have to dash straight to the desk from a meal, when you are so dreadfully lazy, and to remedy this we have fixed up two very fine hammocks in the packing-house loft and there we swing after we have eaten, smoking a cigar, and sometimes having a little doze.’39

In addition to enjoying the relaxed working environment, Engels took advantage of Bremen's more liberal society. He signed up for dancing lessons, combed the city's bookshops (and helped to import some more politically risqué texts), went horse-riding, travelled widely and swam across the Weser, occasionally four times a day. He also took to the testosterone-ridden practice of semi-serious student fencing (Mensurschlager). Quick to take offence and even quicker to defend the honour of friends, family or political ideals, Engels liked his swordplay. ‘I have had two duels here in the last four weeks,’ he glowingly announced in one letter. ‘The first fellow has retracted the insulting words of “stupid” which he said to me after I gave him a box on the ear… I fought with the second fellow yesterday and gave him a real beauty above the brow, running right down from the top, a really first-class prime.’40

Tempering his pugnacity, he also attended chamber concerts, attempted a few of his own musical compositions and joined the Academy of Singing – as much for the chance of meeting young women as exercising his baritone. For Engels was a suavely attractive, if not ruggedly good-looking, fellow: nearly six feet tall, with ‘clear, bright eyes’, sleek dark hair and a very smooth complexion. Encountering him in the 1840s, the German communist Friedrich Lessner described Engels as ‘tall and slim, his movements… quick and vigorous, his manner of speaking brief and decisive, his carriage erect, giving a soldierly touch’.41 Accompanying his good looks came a shade of vanity. Engels's friends recalled him being especially ‘particular about his appearance; he was always trim and scrupulously clean’.42

In future years, his youthful appearance would bring him numerous female admirers but in Bremen he tried to mitigate his boyishness with a determined facial hair strategy. ‘Last Sunday we had a moustache evening [at the town-hall cellars]. For I had sent out a circular to all moustache-capable young men that it was finally time to horrify all philistines, and that could not be done better than by wearing moustaches.’ Ever the poet, Engels composed a suitable toast for the heavy drinking which accompanied the evening.

Philistines shirk the burden of bristle

By shaving their faces as clean as a whistle.

We are not philistines, so we

Can let our mustachios flourish free.

Long life to every Christian

Who bears his moustaches like a man.

And may all philistines be damned

For having moustaches banished and banned.43

This masculine flamboyance constituted more than just fun and games. Joining a choral society and sporting a moustache (of which Engels was inordinately proud just as he would be of his beard in later years) were something of a political statement in the watchful, authoritarian era which followed Metternich's Karlsbad Decrees and then the equally repressive Six Articles of 1832. The denial of freedom of expression in newspapers and political associations resulted in a remarkable politicization of everyday life across Germany with clothes, insignia, music and even facial hair utilized as displays for republican patriotism – which provoked the Bavarian authorities to outlaw moustaches on security grounds. Engels embraced this sotto voce culture of subversion. In addition to his moustache and choral outings, he had Pastor Trevinarus's wife embroider a purse for him in the black, red and gold tricolour of the Lützow volunteers and he developed an ostentatious admiration for the great German composer Beethoven. ‘What a symphony it was last night!’ he wrote to Marie after attending an evening concert of the C Minor and Eroica, ‘You never heard anything like it in your whole life… what a tremendous, youthful, jubilant celebration of freedom by the trombone in the third and fourth movement!’44

For amidst Bremen's cosmopolitan market of ideas, Engels had begun his political journey from Romanticism towards socialism with the discovery of ‘the Berlin party of Young Germany’. Early nineteenth century Europe spawned an eclectic range of ‘young’ movements from Mazzini's La Giovane Italia to Lord John Manners’ Young England cabal of aristocratic Tories to the Young Ireland republican circle, each of them championing a revival of patriotic sentiment based around a romanticized idea of nationhood. However, Junges Deutschland was far less of an identifiable political project and more a loosely aligned, ‘realist’ literary grouping, centred around the dissident and radical-liberal poet Ludwig Borne. Their unwritten manifesto demanded that the romantic Age of Art give way to the Age of Action, and Börne, a fierce opponent of Metternich's authoritarianism, was scathing towards the craven, political quietism which had been adopted by Goethe and other high-minded priests of Romanticism. ‘Heaven has given you a tongue of fire, but have you ever defended justice?’ he demanded of the Sage of Weimar whose career he ridiculed for its courtier-like servility towards princes and patrons.45

Börne's cause was cultural and intellectual freedom under a system of modern liberal governance, and he was highly dismissive of the nostalgic forests-and-ruins conservatism of traditional Romanticism. Exiled in Paris, having run foul of Metternich's censors, he moved towards republican politics whilst lobbing sarcastic barbs at the Prussian occupation of the Rhineland. Joining Borne in the Young Germany firmament were the poet Heinrich Heine, the novelist Heinrich Laube and the journalist Karl Gutzkow. Gutzkow's notoriety came from his 1835 novel, Wally the Skeptic, which combined a racy narrative of sexual liberation with religious blasphemy and cultural emancipation. The lengthy ramblings of his ‘new woman’ heroine, Wally – with her liberal sentiments on marriage, domesticity and the meaning of the Bible – managed to encompass just about every known anathema to Biedermeier society. Metternich was not slow to act on such a dangerous affront to public morals and political stability and in 1835 he had the Diet of the German Confederation condemn the entire oeuvre of Heine, Gutzkow and Laube.

Engels identified enthusiastically with Young Germany's rejection of romanticized medievalism. Although he continued to be drawn to the heroic myths of the past on a literary level, he was equally convinced that Germany's political future could not entail a retreat to the feudal nostalgia of the Middle Ages. Instead, he expressed sympathy for a programme of radical, progressive patriotism which looked enticingly possible in the early years of the reign of Frederick William III. This was not a call for democracy but for the liberation of Germany from the parochialism of feudal, petty kingdoms and their absolutist rulers. Above all, as Engels wrote, what Young Germany wanted was ‘participation by the people in the administration of the state, that is, constitutional matters; further, emancipation of the Jews, abolition of all religious compulsion, of all hereditary aristocracy, etc. Who can have anything against that?’46

Augmenting the radicalism of Young Germany, Engels's political consciousness was aroused by the poetry of the man he called ‘the genius, the prophet’, Percy Bysshe Shelley (whom he read together with Byron and Coleridge).47 No doubt the office-bound Engels was excited by the heroic bravado of Shelley's rebellious, priapic lifestyle: the breach with his reactionary father, the d

oomed love affairs and devil-may-care nonchalance. But what also attracted him was Shelley's political philosophy. Not yet for Engels the ‘recognizably pre-Marxist’ writings of An Address to the People on the Death of the Princess Charlotte (1817) which, in contrasting public reaction to a royal death with the case of three recently executed labourers, directly connected political oppression to economic exploitation.48 Rather, at this stage of his thinking, Engels was drawn to the radical republican, antireligious, socially liberal creed which Shelley explored in Queen Mab (1812):

Nature rejects the monarch, not the man;

The subject, not the citizen: for kings

And subjects, mutual foes, forever play

A losing game into each other's hands,

Whose stakes are vice and misery.

No doubt he also enjoyed Shelley's thoughts on political economy.

Commerce! Beneath whose poison-breathing shade

No solitary virtue dares to spring;

But poverty and wealth with equal hand

Scatter their withering curses, and unfold

The doors of premature and violent death,

Here was an idea of personal liberation tailor-made for Engels the radical romantic doomed to a life of commerce. Yet Shelley's celebration of political freedom in his ‘Ode to Liberty’ also touched a chord with Engels who responded with an 1840 poem, ‘An Evening’ (topped with Shelley's epigram, ‘Tomorrow comes!’)

Frock-Coated Communist

Frock-Coated Communist